In a flash of curiosity, your correspondent developed an urge to look back into Hong Kong’s history through how the city has named its buildings over the past 70 years, and the handy tool with which to undertake this flight of fancy is none other than “Names of Buildings”, a regularly updated report published by the Rating and Valuations Department (RVD).

The

analysis focused on the residential and commercial buildings of the private

sector only1, covering some 12,000 structures. Since all buildings

completed before 1945 were not identified by their years of completion, we will

just put them under the “Pre1950s” group for our analysis. Also worth noting is

that since we are still early in the 2020s, this category will have much

smaller sample population than other decades:

|

Chart 1: by decade of completion, 1970s was the peak of

Hong Kong, constructions |

It is clear from above that the 1970s was the height of Hong Kong’s population growth, with 3,165 completions, followed by the 80s (3,070), just these two decades constituted around 50% of all buildings constructed in the territory.

Let’s

now delve into the wondrous world of names used to describe these thousands of

structures:

|

Chart 2, Most buildings have bilingual names, very few

were purely known in Chinese, even in the early years |

|

It is interesting to note that a substantial portion of buildings (38%) had only English names on the register in the pre-1950s era! This phenomenon receded in the subsequent decades but is now making a comeback with the 2020s now seeing 1/5 buildings with English only names again – is it increased education standards of the population, or is it more residential sale marketing gimmicks?

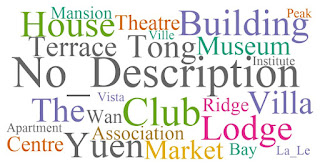

Below, your correspondent has generated word clouds of descriptions of building names to better visualize what dominated each era2.

Transliteration

very common in the pre-50s

The

early days of Hong Kong, it was common to have names that identified with the

property per se, with no need to call it a building or a house, such as:

Westcrag, Bethanie. The other very popular way to describe a building is use

straight Chinese transliteration of the description of the structure, where

Yuen means Garden, and Tong means Hall, while Wan means Bay, for example –

these are all prevalent names of the time:

|

Chart 3, Pre-1950s buildings – no description is good

description |

Functional

50s – all residential

After the defeat of the Nationalists in the mainland in late 1940s, there was a wave of immigrants coming to Hong Kong which drove a massive need for new residential housing to accommodate the new arrivals. This explains the dominance of residential themed building descriptions as shown here:

1960s saw emergence of HK’s industrial base

The continued high growth in population, coupled with the government

initiative to clear out the squatter housing by hill sides meant the 1960s continuing

the trend started a decade before – more residential buildings:

|

Chart 5, Continued dominance of the most common

descriptions in the 1960s |

But as Hong Kong started to grow and take on a manufacturing role, we started to see industrial themed descriptions come to prominence (factory) and commercial buildings related to overseas visitors (hotel) also came to the fore. In fact, the export weighting of GDP rose from 30%s in the 60s to over 50% in the next two decades, until service sector took off from the 1980s onwards:

|

Chart 6, Share of Exports reached a high in the 60s

|

Large

estates becoming common in 1970s

The most common descriptions of the last two decades continued to dominate in the 1970s – Building, Mansion, House remained the top 3 monikers, but a new trend started emerging – the popularizing of larger housing estates, as seen in the names Centre, Tower, and City during this period:

Chart 7, Most common description of building name in Hong Kong,1970s |

Godown

and Factory also rose to the top, suggesting the popularity of industrial and

import/export related buildings were increasing, and pointing to the strong

rise in HK’s manufacturing prowess in the 70s. But this decade will also be

remembered as the peak of the long reign of the term ‘Building’, when it was

used in at least 3x as many buildings as the next popular construction description:

|

Chart 8, ‘Building’ was the most popular description in

building names, during 1960-80s |

Emergence of lifestyle names in the 1980s

Perhaps due to more large estates being built, the frequency of the description ‘House’ fell in prominence in the 1980s. Also interesting, although not seen in the word cloud below is the emergence of lifestyle related words such as Chalet, Ridge, Beach, Castle, Lookout, Walk, Cliff, Grove, Cove, Monte, Summit… largely of the holiday and nature variety in their aspirations.

Chart 9, Most common description of building name in Hong Kong, 1980s |

Interesting enough, some of the transliteration type descriptions popular from the pre-1950s era were still being used, such as Yuen, Lau, Chuen, Tsuen, Tong, although the last three did no appear in the word cloud above.

Big is beautiful in the 1990s

As large estates and mega commercial complexes became the new favourite type of construction projects, coupled with big developers celebrating the peak of the property bubble in early/mid 1990s that accompanied Hong Kong’s brimming economic/cultural confidence and conspicuous consumption, it is no surprise that the term Centre became the top description in building names:

Chart 10, large estate descriptions rose in prominence in 1990s |

Other descriptions associated with large projects were also more commonly seen, such as Plaza, Square, and City. Another factor that helped the theme could be the strong last burst in population growth in the 90s, providing the needed fuel in demand as well as strong price gains:

|

Chart 11, 1990s saw the last strong burst in

immigration and thus population growth in HK |

Necessity

– the mother of all creativity in the 2000s

The

Asian Financial Crisis and the subsequent long property crash in Hong Kong

might have been the needed trigger to get developers working hard on both

quality and ingenuity in naming their products – we saw some very exciting

trends emerging in this period in how projects were named:

‘No

Description’

returns – that is, projects not ending in a description such as building or

house, but boldly go by names alone, eg. Oscar by the Sea, Noah’s Ark, Aqua

Blue, Elements;

Numbers

as descriptions,

such as SOHO 88, 99 Hennessy, One Silversea;

Definite

articles

(The/ La/ Le) everywhere, and in their own sub genres! Here are some quick

categories of interest:

·

Paradise

islands – The Capri,

The Aegean, The Giverny, and The Monet!

·

All

that glitter – The

Spectacle, The Sparkle, The Cullinan!

·

Top

of the world – The

Top, The Zenith, The Dynasty, The Centrium!

·

The

bizarre – The

Loop, The Celebrity, The Masterpiece!

· The exotic - La Maison Du Nord, Le Bleu Deux (after Le Bleu … naturally!)

|

Chart 12, the 2000s saw a burst of creativity in

building nomenclature |

Privileged

upbringing brings bold new names – the 2010s

The ‘No Description’ category

remains at the top in building names, but WHAT ON EARTH is Double Cove Starview

Prime? Other themed names that stand out include those aspiring to exclusive

new world destinations, such as: St. Moritz, St. Barts, Gramercy, Malibu. There

were even musical themed names as well: Diva, Solo, Aria, Harmony, Crescendo

(not in word cloud):

Other interesting observations for the 2010s include: continued Latin invasion, such as La Splendeur, Le Prestige; and even more numbers with 2gether, K11, W668, CORE45, etc.

We surmise that these very diverse and interesting new names were perhaps brought on by a new generation of developer scions heading up their family empires, having born with silver spoons and sent to exclusive top universities for education, are full and proper integrated into the world’s best culture and lifestyles had to offer.

Short but good start to

the 2020s

We decided to add a 2020s category as well, even though we are only 3 years into the new decade. As such, trends are still emerging, but we continue to see strengthening of trends started in the 2010s: more use of numbers – such as 99 Commons, LP6; and still wackier names in the ‘No Description’ category – including Sugar+ , Sea to Sky, K-Farm, W Mega, and even OMA OMA!

Chart 14, no-description and numbers continue to be the dominant theme in 2020s so far |

Looking back, our review of the trends and fashions that shaped how Hong Kong named its buildings shows how the city’s economy constantly transformed, and how we went from small and functional to large and high density, from confident world beater to more nuanced cultural depths… surely the coming years will reveal to us what the world has in hold for us all.

1 Private

sector here means buildings excluding government subsidised flats (PRH

& HOS), government and public venues, hospitals and homes, fire and police stations,

as well as charities, religious and cultural premises.

2 Each building description includes its plural form (e.g. ‘Villa’ includes also ‘Villas’), and ‘8888’ is used to label buildings that have numbers in their names (1, 2, One etc.).

The author would like to thank Lam Chin Ming Matthew from The Chinese University of Hong Kong majoring in Quantitative Finance and Risk Management Science for assisting in data collection, analysis, and drafting of this article.

Thanks for being a beacon of positivity, uplifting your readers.

回覆刪除